Justin Pearson interviews Jesse Keeler about Black Cat #13…

Here is the most recent installment of Justin Pearson’s “I Hung Around In Your Soundtrack”, where he interviews a person from each Three One G release and covers relevant ground on the album and the artist. This one is with Jesse Keeler, who started Black Cat #13, which was Three One G’s thirteenth release.

“I Hung Around In Your Soundtrack” Part 13 by Justin Pearson

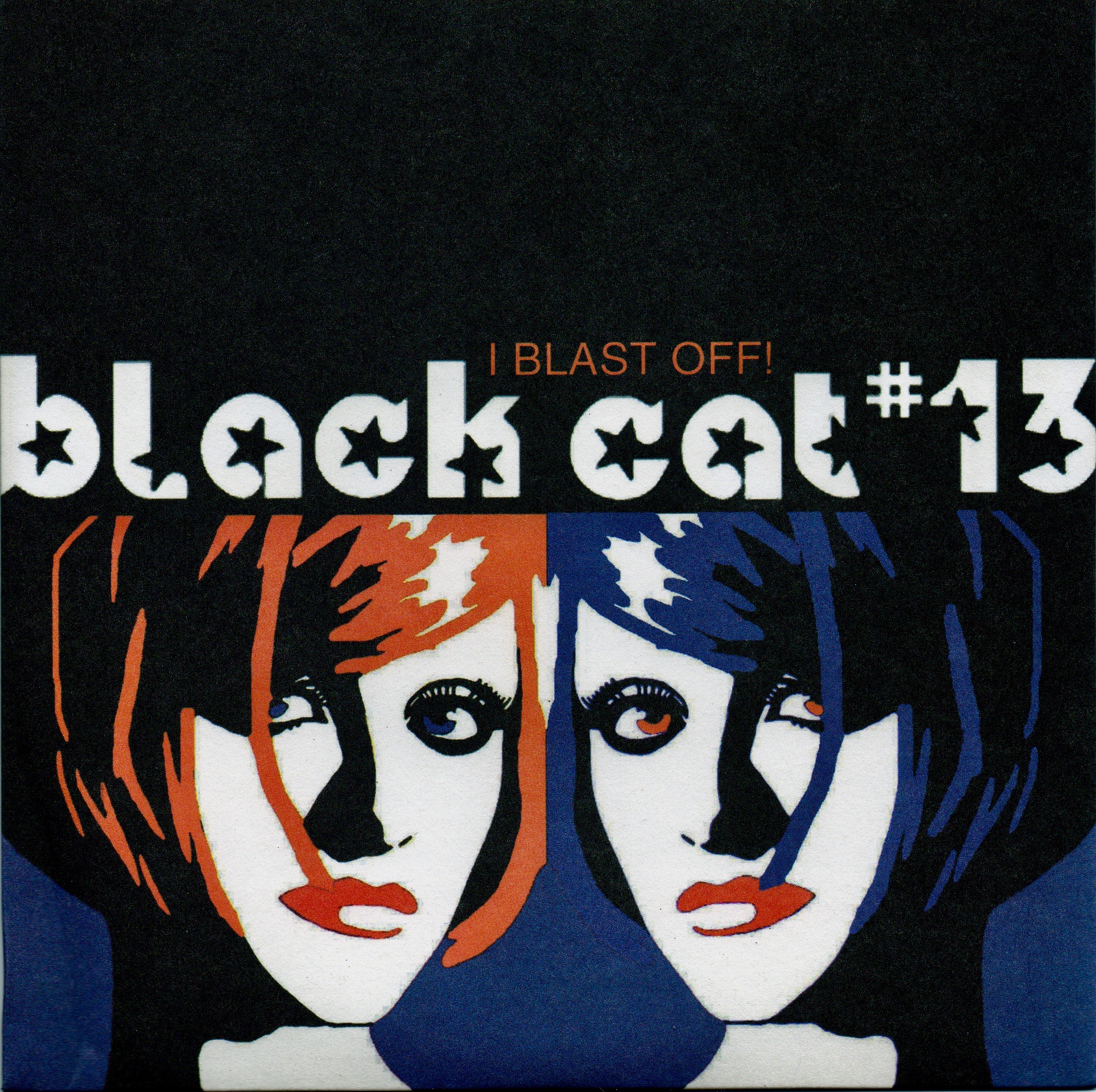

Black Cat #13 “I Blast Off” EP

When Three One G got around to the label’s thirteenth release, I was still drawing influences from different places, and had latched onto an idea that Dischord– which was to only release bands from D.C.– but to only release stuff by bands from California. Black Cat #13 managed to throw that idea out the window, which was fine by me. It was Jesse Keeler who really helped redefine the basic idea of what the label was becoming, which was more so a family or community. He and I had created a rare long-distance friendship, which has lasted close to two decades. I thought Black Cat #13 was a perfect band for what the label had become at that point, but I also felt that the people in the band were just as important as the music, and the camaraderie was the definition of the label.

The band and their EP was cute and creepy. With almost Melt Banana-like lyrics and vocals, and heavy synth-driven riffs, the band seemed to embody both the past and the future of punk music. Drawing relative influences from various places, they also managed to put a cover of “War #1” by Struggle, which was the first band I played in. Struggle released records on Ebullition, which was in part why I started Three One G. The quality of the label was something I aspired to, but I also felt an opposition to what felt at times to me like an overtly uniform and almost conservative punk community. With Black Cat #13, it was refreshing to hear a No Wave rendition of my leftist political hardcore band, and their artwork on the EP was one step away from the drab, depressing imagery I grew up using for my own band. But more so, the album, and the band in general, had a unique air about things well beyond the music. Back then, to me, they seemed almost like a circuit-bent video game.

Black Cat #13 was fairly short lived, but in that time, they managed to do a U.S. tour with The Locust, and shared the stages with other influential and now legendary bands such as Arab On Radar and Jenny Piccolo, which go back to the theme of the Three One G community. I’m grateful that I’ve remained friends with Jesse Keeler over all these years, and glad that his band was part of the early part of Three One G.

Interview with Jesse Keeler: January 2018

Justin Pearson: Initially when I started Three One G, I had this idea based off of how Dischord was, and how they only released DC bands. But I was planning to go with a California theme. However, you all screwed that up pretty quick in the game, given that the Black Cat #13 release was number thirteen. It made me sort of reevaluate the concept that Dischord had, as well as my initial idea of keeping things California themed. I wanted to branch out, but also to reflect inwards and make it more of a family than anything else. At the time, maybe twenty years ago, we became friends– sort of by chance, or I suppose destiny if you want to call it that. Nonetheless, we instantly became family, and here we are many years later talking about your relationship to Three One G. Would you care to talk about being part of the Three One G family, how it seemed like something that was supposed to happen, and then talk a bit about you starting the band and your musical background?

Jesse Keeler: Of course. Three One G really did have that vibe you were aiming for. I’d say that it’s rare when being on a label means something, and to this day, I still have people ask about it or mention it in a different way than other labels I’ve released stuff on. I know when I started doing record for Warner Brothers, I had this impression of what that meant based on seeing their logo in my dad’s record collection. It meant I was part of that in some small way, although comparing the two is like Walmart to Fendi or something… which would make you hardcore Karl Lagerfield. I’d say our pre-Internet friendship, started with a “to who it may concern” type paper letter is a singular experience in my life. We had been friends for many years when you asked if Black Cat #13 would be into doing a record for you, and it seemed just about as natural as could be. I’ve been making music since 79, when I was 3 years old and started playing the drums in my grandparent’s basement. My dad and grandmother were musicians and it just seemed like what people did. When I started playing in bands, it was as a guitar player, but drums are still to me what I consider my real instrument. Black Cat #13 was started by my friend Mark McLean and I while we were both in other bands, me as a guitar player. I really wanted to play drums and he was a very driven bass player with similar, or at least complimentary tastes in music. We wrote a bunch of songs on bass and drums, then asked our girlfriends to also be in the band with us, his doing vocals and mine on synth. Once that happened, we were really motivated by how it sounded and it just snowballed from there.

JP: You definitely meshed with everyone in San Diego. You felt like a San Diegan for sure. But let’s move away from the Karl Lagerfield stuff and talk about the band’s musicianship and aesthetic that you all went for. A lot of very interesting stuff was happening at that time musically. There was a sort of no wave resurgence and since it was pre-social media when the band was active, everything was still a bit more special and underground. As a drummer, but also just as an artist, what were the elements that influenced you to do what you did at that point? Maybe not just musically, but more so in life at that point.

JK: I did feel pretty at home there, and at the time, I really didn’t feel at home in Canada. There was something happening in music down there, and when I was back in Canada, I brought you all with me. No wave as a concept is something I didn’t really learn about until many years later, and it definitely made sense when I did, but I think the sound of the band had more to do with our writing process than anything. Because Mark and I wrote the songs with just the bass and drums, I think we were trying to fill all the sonic holes ourselves. The vocals and synths afterward gave it depth, but as musicians there was a lot the two of us wanted to get out. Maybe we were just afraid of space? I hadn’t got to play drums in a band before, so I must have had something to prove. I would play drums for hours every day, whether or not we were rehearsing. Sometimes I would just get something looping on a synth and play along with that until I couldn’t keep time anymore. I guess I was chasing a feeling, maybe from the music and maybe just in myself. I don’t remember being particularly happy or sad, but it was definitely fun. Somewhere there is a box full of cassette tape recordings I made back then that are basically just drum solos over noise.

JP: I have to say, I love the writing of a good drum and bass duo. I wonder if that Black Cat #13 stuff translated in to the material that you have written in Death From Above 1979. Nonetheless, I do think you and a lot of bands associated with Three One G were influenced by our peers of a generation or so prior. The No Wave stuff that was before us, certainly paved the way for music that spoke to us all, and subconsciously made its way into what a lot of us were doing. I mean this as a complete compliment, but by adding Lindsay as a vocalist for the band seemed to fit right in line with your potential musical predecessors. Was that a conscious move, or just coincidence that the band’s lineup was two couples? And as for the comment about being happy or sad, I think for a lot of us, we did what we did because we absolutely had to, for some sort of survival in the world that we lived in. A lot of what we all did, and maybe for some of, still do, is not always something that is going to make us happy. A lot of art, and specifically music can come off as a civil duty in some ways. And without us all knowing, we were speaking to people without using language. We went through the trenches of culture(s) and connected with so many people back then. Do you feel like you are on a similar track? I suppose with the success you’ve had over the years post Black Cat #13, do you still feel that you connect with people like you did back then?

JK: Oh, it absolutely laid the groundwork in my mind for Death From Above, plus I am still literally using the same amps Black Cat #13 had out on tour opening for The Locust. With influences that reach further back, that’s usually something I’ve realized down the road, being influenced by an idea born 3 or 4 generations earlier, then personally discovering that initial source of it later on and being amazed. I think the way Lindsey deciphered her lyrics after recording the song really helped with how it came together. Almost letting the song itself decide what it was about, if that makes sense. We did one tour with a fill in singer because she couldn’t come on the road, and it was a totally different vibe. That experience probably helped us appreciate what she was doing more. Maybe what has kept me making music is this abstract daydream, where I can make something I like so much that I don’t feel the need to make any more. My conscious mind knows it’s not going to happen, but I see myself trying to find it anyway. The closest you can get is when you write something new, and it feels like it’s the best thing you’ve ever done. Everyone who has made music knows that feeling. As far as that musical connection now, so much has changed since back then, in terms of the relationship people have with the music they listen to and the artists making it, I don’t know if it could be the same. Imagine an art gallery in 1982, and someone is posting iPhone selfies with a new Basquiat piece no one has seen before, tagging him and unconsciously making that moment into some sort of social capital. Maybe it’s my age, but I can’t relate to having that sort of relationship with any art. The whole idea of “fans” is so abstract to me until I’m talking to them face to face.

JP: It is strange to think about the subconscious and how things panned out in retrospect. I think if anything, that shows an air of sincerity. I also think that timing is such an important factor. But you are correct about how it can never be as it once was. The iPhone reference in context to a new Basquiat piece is similar to things that I ponder almost on a daily basis. This idea or concept might be why people tend to long for nostalgia. It’s one thing to be nostalgic and try to recreate something, and something entirely different to be influenced by something and create something on accident. I see this in the stuff you have done more recently, specifically with MSTRKRFT, collaborating with Sonny Kay, Jake Bannon, etc. I suppose there are artists who do whatever they want, and do it for themselves, and then there are the others.

JK: Making music purely for yourself is something I think is easy in isolation, and then probably comes from a place of confidence when what you’re doing is more visible. I know through the years I have understood that more, and that I’ve had to self-impose that isolation to stay in a place where I feel more creatively free. That MSTRKRFT record was something we felt free to do because we didn’t feel like anyone was paying attention. We had completely finished it before showing it to anyone, and the record label accepted it as it was. I know we couldn’t have done it any other way. My art gallery reference was based somewhat on real life. I was in a gallery recently and noticed that nearly everyone was taking photographs, and I wondered what those photos were for. I also see it when watching my kids do little shows at school. Parents are often looking at the screen while filming more than the event actually taking place in front of them. That sort of relationship to experiences has to affect creativity, thinking about how something will be used rather than just creating it for its own sake. I think my own nostalgia is for a feeling I remember having.

JP: Do you see Black Cat #13 as a launching point for stuff that came later? Or a stepping stone in the process, possibly since the band was pretty short lived? I suppose there are elements of what you did back then and what you do now, but with a more of a modern approach.

JK: It was definitely the launching point for me. It was one of the first things I had done that people really took seriously. We put out lots of records, toured with bands we loved and got asked to do more things than we had time for, and all that from doing something that wasn’t really intended to succeed. Every band around us was the sort of typical guitar/guitar/bass/drum/singer model, and we decided to try something else. That it worked at all taught me that those conventions weren’t necessary, and obviously I applied that lesson making Death From Above. Of course the focus can’t just be about the form, the content needs to be right as well, but it helps me creatively if there are some sonic shortcomings to overcome. Even my drum setup for that band was just kick/floor tom/snare. Trying to be creative within self-imposed limitations is more fun and I guess focused for me.

JP: I do think it’s incredibly relevant to address the sort of seminal petri dish where you were able to grow the molecular matter that is what has become of you and your work. For me, and Three One G, it has been such an interesting thing to see, as well as an honor to be part of that launching point. And I’m certainly glad it was you that broke my initial California only idea I had for the label, because Three One G got to work with a lot of amazing people after we released your EP. I do wish that Black Cat #13 was able to do more, but as we both know, back then, at a much younger age, people have to grow up and find their specific calling. I’m certainly glad that we were able to collaborate on so much, be it touring together, photography, releasing music, etc. But what I’m most grateful for is that you are still progressing as an artist. Thank you for that.

JK: My time in San Diego, my relationship with Three One G… I carry the things I learned in that time with me into everything I do. You can call it a petri dish, but for me it was more like a musical iron lung, letting me breathe. I know I’ve thanked you before, but allow me to thank you again here as well.

Other interviews:

Unbroken

Swing Kids

The Locust

Jenny Piccolo

The Festival of Dead Deer