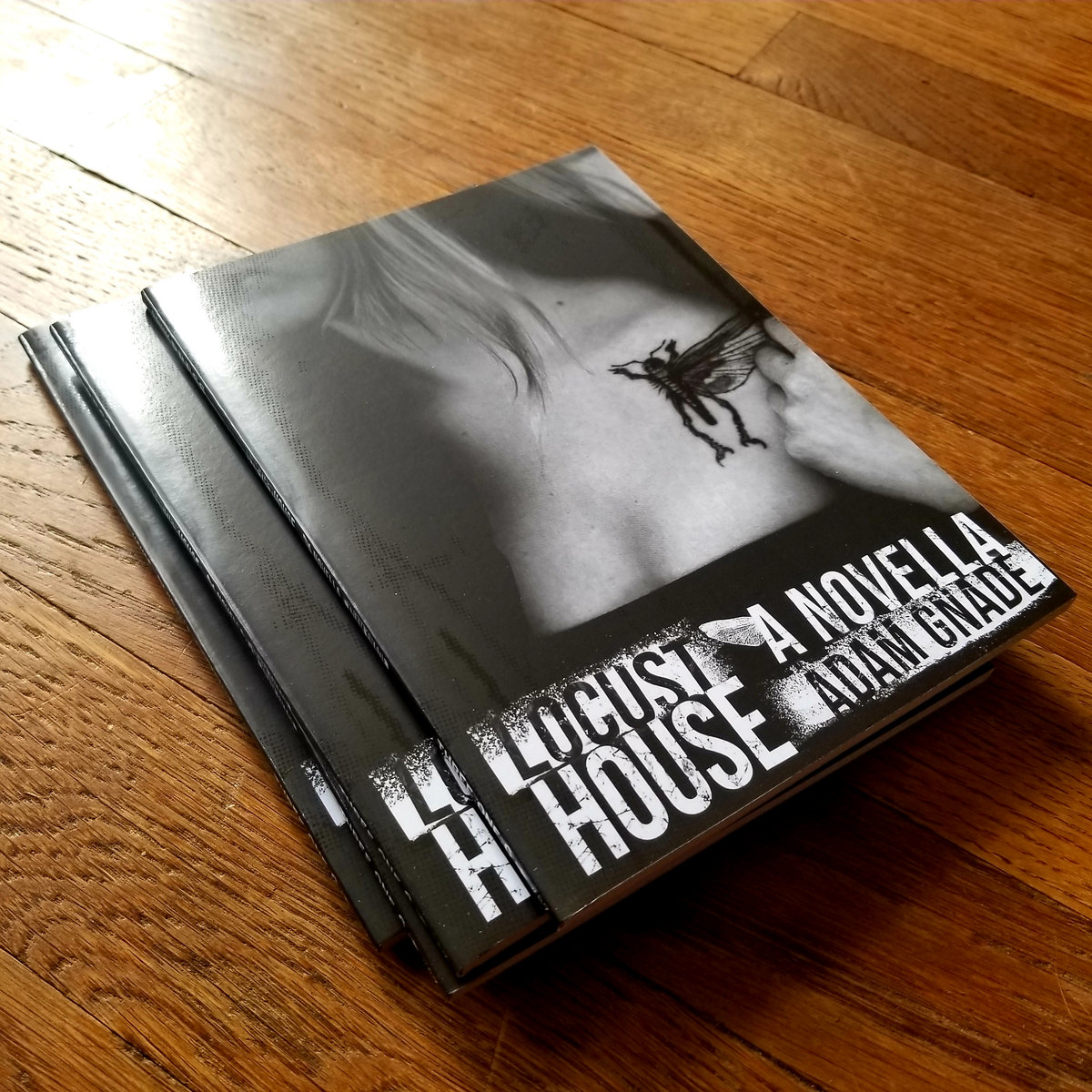

She Wanted Violence, Happy Birthday to Locust House by Adam Gnade, 4/5/2016

Note: this is an excerpt from Adam Gnade’s novella Locust House, released six years ago today by Three One G and Pioneers Press

Chapter 1, The Adventures of Agnes McCanty

Looking back, Agnes McCanty would come to see March 29th, 2002 as a day broken into three stages:

1) Standing at the gravesite of Michael the Bear.

2) A view of the sea from atop the rollercoaster then sex with Steven Boone in the backroom of the Halloween store.

3) The final night on E Street and how much she bled and how she felt like an arm held out a speeding car window.

The first: Standing at the gravesite of Michael the Bear in Sherman Heights—his bronze and black Keller-Holland casket like a train car, eye-level for a girl of five foot one, blocking out the sun which glared around it, golden but soft, dusk coming.

Agnes thought of the man who lay inside. Michael the Bear, her father’s uncle, an Irishman (raised in England), though 40 years in the States (Pacific Grove [10 years], Watsonville [12], then San Diego [18]). Before that a pub cook in Coventry (two years) then an RAF pilot in the Second World War (26 months). Michael the Bear, the man who cared for Agnes after her mother passed away (breast cancer) and her father went to jail (for his brother-in-law’s murder).

Michael the Bear stepped in, selfless, noble, loyal to Agnes—forever loyal, his defining characteristic. What else? He was strong but wouldn’t stoop to violence (which he told Agnes was unbecoming, as was backbiting, complaining, self-pity, selfishness). He was classy, she decided, yes, whatever classy meant he was that. This had nothing to do with money, which he had, but rather an overriding trait of his upbringing, his generation, and his content of character.

Michael the Bear was a man who liked people, who quietly loved anyone fighting to do a good thing—whatever it was, the goal mattered less than the path there. The final objective itself was unimportant, or secondary.

Agnes stood at the gravesite next to her cousins (who smelled like cigarettes and shampoo) and thought of his face—dark, dignified, high forehead, crow’s feet around the eyes, hair swept back in a mane like a lion’s, a voice like Liam Neeson’s, deep and slow and resonate with bass—a calm voice, husky on the “w”s and soft vowels, telling her she was a good woman, that she had grown up well, that he missed her around the house but understood her absence.

The day he died Agnes found the body.

The door was locked but she had a key and she stopped in on the way to band practice the day the wildfires swept over East County.

The night before she had dreamt of skulls of sheep washing up on the beach—though huge, whale-size, rolling in the surf.

It was a dry day and it was hot and you could smell smoke and ash in the air from the blaze. Somewhere down the street a dog barked—yipped—as she unlocked the front door.

Agnes heard the sound of the breeze in the eucalyptus.

She pulled the door shut behind her.

The front room was quiet and still and there were dust motes moving in the light of the side-yard window.

She called his name.

The mouth of the hallway was dark—a black rectangle, open, featureless. She stepped into it and called out to him again as she walked down the hall.

In the bedroom Michael the Bear was under the big denim quilt. He … no, not he, she thought, his body, it, not he, was facing the wall. A giant, six foot four even at his age, a flattened mountain or a cinder cone, motionless. His body was still in a way that the living never are.

The room was cold.

She dropped to her knees.

Michael the Bear was 82 and it was “coming” (her cousin Mary Lynn said on the car ride to the cemetery) but it would never happen today, some other day perhaps, not today, today would be fine, he would be here today. Anyway, why say goodbye to the living? Why sum up your time with someone when their time has not come?

“Hummingbird” was his name for her. Riding on his big shoulders at the Del Mar Fair, age four, talking in her high, piping voice, tiny hands too tight around his neck, but he didn’t mind. He loved her with a burning pride, a strong, tremendous, substantial love; she couldn’t hurt him. No one could. He was a stone, a castle wall, a locked drawbridge but a drawbridge that would open if she (or anyone worthwhile) asked. He was tough without being hard and that was the thing that made her feel safest.

Over the years Michael the Bear told Agnes some variation of the following in his slow, rolling, measured tone: “Hummingbird, if you can grow up tough without becoming mean or bitter or sour or cynical you’ll do just fine.” He said things like, “Remember Hummingbird, life is about finding as much happiness as you can without hurting anyone in the process. You won’t find the meaning of life (but you’ll look, if you’re any good, and I know you are). What you will find is truths like that. True ways to live. That is one of mine, and it can be yours as well. Enjoy life violently but never be violent. Violence is the tool of cowards.”

Agnes loved Michael the Bear with a fierceness she would not begin to understand until she was a parent herself. It was the true, animal fierceness of a blind cub in a den, of the small protected by the strong. Now that he was gone (gone entirely, and unavailable to her) nothing she could do would allow her to speak to him again, which is what she wanted more than anything. Less to say goodbye than to ask him where he was; she couldn’t imagine him so far gone as to be nowhere, as to not exist. His body, that was nothing, where was he? Where was the big, honest, courageous, tireless spirit that was Michael the Bear? A good thing like that doesn’t die.

” … and now safe … in heaven … with God,” said the preacher. He didn’t know Michael the Bear. He was hired from St.-Matthew’s-by-the-Sea. A hired man. “Martin Schrader,” he called him. Who was Martin Schrader? Michael Schroeder was Michael the Bear. There is no Martin Schrader, no, not here, not lying in there. “Mr. Schrader … a good man … in God’s providence … after a long … fine life.” Droning, enjoying a long pause and the sound of his own voice, but disinterested in the meaning. Agnes smelled rum on his breath on the walk across the lawn.

The smell of the flowers was sickening. She wanted nothing more than to set fire to the pile of them and push the preacher down into the blaze. She wanted to burn him to cinders for giving Michael the Bear an improper send-off. Stomp on his skull ’til it smashed flat and his brains burst out like cold pork gravy. Pull his spine from his body and beat the ground with it. Beat the ground and mourn Michael the Bear. Mourn him with blood speckling her arms, misting the air.

Agnes felt like a monster. She wanted to scream. She wanted to let loose her rage until the whole world shook. Agnes couldn’t be kind like Michael the Bear. Not now. She wanted violence. She wanted to be violence.

The next few hours are remembered in a gauzy flash of images.

They were as follows:

Cresting the hill of the Giant Dipper rollercoaster at Belmont Park with her cousins Daniella and Mary Lynn after the funeral. A redheaded boy her age sitting in the coaster car next to her who smelled like old pasta floating in a pot of water. He held the metal bar in front of him and looked seasick as they rose up the track.

Earlier, on the car ride back from the cemetery, the green blur of Balboa Park flashing by:

“We have to kill an hour,” said Mary Lynn, driving. She wore big sunglasses with white plastic frames and her dyed blonde hair moved around her face in the breeze.

Daniella leaned in from the backseat. Cigarette breath. “Hotbox Yoda the Toyota and ride the rollercoaster?”

“Hells yeah. Let’s do it. Agnes?”

“Huh?”

“Agnes, you wanna get stoned and ride the Dipper?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

And it didn’t.

Or did it?

She sat in the beach parking lot while her cousins laughed and passed the pipe from the front-seat to the back.

Did it matter?

What mattered?

It didn’t matter.

Then: after the clacking assent up the rollercoaster track and before the plunge downwards, there was a view of the sea—silvery and wind-chopped, cold, vast, rolling with long lines of swell.

It never ends, thought Agnes.

Next: the drop down and her hair blowing straight back and the tightening of her stomach muscles as her cousins screamed happily, arms held up. They took the turn hard, the wheels rattling, jostling on the track, the wind in her face, gritting her jaw, strained, nauseous.

Next: ditching her cousins at the amusement park in the dark of the arcade, Agnes walked down Mission Boulevard alone with the evening traffic all around and the wind whipping her hair into her eyes. Storefronts, surf shops, beach bars, grains of sand under her shoes on the sidewalk, traffic lights in the dusk.

Next: asking her boyfriend Steven for a ride home at his uncle Carl’s Halloween store.

“I’m sorry to ask but—”

“No, it’s cool, that works. Come back here a sec.”

“Here?”

“Just c’mon.”

Steven took her hand and they walked past the walls of masks—ghoulish faces, hairy, mouths open, cut-out holes for eyes, screaming silently, devil beards, worms and maggots nestling in wounds, bloody teeth, fanged, rubbery, howling without sound, horrible mouths—and into the back room while Big Marcos the new hire sat at the register reading a comic book. There was gray light (a fading light) through the windows, and Big Marcos, frowning down at the book, turning the pages with a soft, fat hand as Spider-Man swung through the city after the Green Goblin, casting his webs left and right.

Next: in the back room, Steven, shoving her forward against the counting desk on her belly, her skirt pulled up to her waist, her panties to her ankles, and pushing up inside her, before she was ready.

“Slower,” she said. “Ow, Steven. Slow down.”

“I’m … trying.”

“Take your … time. Slower. Steven! Not yet. No … ”

It was over fast. One hand on her waist, gripping, his nails digging into her flesh, the other clawing her right breast until it hurt, his hips smacking against her, and he came into Agnes “like a dish soap bottle squeezed into a tub of warm water,” he told Big Marcos with a laugh while Agnes cleaned up in the bathroom. “Agnes, she’s a mess but she’s a hot little fuck,” he said. “Check it, take my keys. Drive her home. If you want to fuck her you totally can. I bet she’d at least suck your dick. My brother Ted’s in town. The three of us should get her drunk and try to run a train on that little bitch.” (Big Marcos, overwhelmed and upset by the proposition, took a smoke break before driving Agnes home. The next day he would quit Steven’s uncle’s Halloween store and apply [unsuccessfully] at the Clairemont Party City before landing his dream job at the Karl Strauss Brewery by the freeway. Eight years later he would add Steven on Facebook and send him the following message: “Dude, that shit you said about your girlfriend and us having sex with her? That was so not okay. I’ve been thinking about that for years and I had to get it out. That was a shitty, evil thing to say.” The message received no reply and Big Marcos was promptly unfriended.)

On the drive back to Golden Hill, Big Marcos hummed along with the car stereo while Agnes sat in the passenger seat and felt small and used-up and unimportant. To clear her mind, she thought of Michael the Bear’s favorite things to cook:

1) Once a week: lasagna with Italian sausage. Later, as a substitution, butternut squash ravioli with brown butter, sage, and shaved parmesan when she quit eating meat. For both: side of garlic bread. A spinach and cabbage salad with halved red grapes, kalamata olives, marinated artichoke hearts, and goat cheese (later, baked tofu).

2) On the rare chilly nights in the winter they would sit around the small kitchen table and eat thick split pea soup cooked with carrots and bacon (and, later, liquid smoke or Bacos). On the side: sourdough bread. The serving of the bread: butter and a squeeze of lemon, a result of Michael the Bear’s four years working at Bozic’s (1976-1980), a seafood restaurant on Clairemont Mesa Boulevard.

On summer days when it was too hot to move he made gazpacho with a pitcher of strawberry lemonade. For dessert: peach ice cream garnished with a sprig of mint. Michael the Bear maintained what he called a “Victory Garden,” and with San Diego’s long growing season a good portion of each meal came from what he grew. She saw him standing at the kitchen counter of the old North Park house, slicing lemons in the late-afternoon light, saying, “Agnes, everyone must know how to grow their own food. When you cut yourself off from that you shut the door on something older than history, something important and deep to our character.”

Agnes thought of his meals and his happiness (and how serious he was) as he prepared them.

She stared out the window at the growing dark, the sunset behind the car like a wall of fire consuming the Earth.

Don’t fucking cry, she told herself. Not in front of him.

Stopped at a traffic light across from the Nuevo Cristo church she saw a wedding party push open the big doors and come out from the gold-lit square of the hall and down the steps, the bride in front, holding up her dress to walk.

She imagined Michael the Bear giving her away at her own wedding. How proud he would be (and how stirred his big heart) as he answered the words, “Who gives this woman away?”

“That would be me.”

It was night now and the bride’s gown was so white it was nearly blue, like snow glowing against her dark skin and all the black suits and dresses and gray stone around her.

They made a left at the light.

“Isn’t it kind of late in the day for a wedding?” she asked Big Marcos, who drove with one hand on the wheel, the other on his right thigh, tapping along to the radio.

He shrugged. He didn’t know.

The singer on the radio was singing that if he could find that Heina and that Sancho that she’s found, he would pop a cap in Sancho and smack her down, and Agnes wanted to die. For the first time in her life she wanted to die.

Big Marcos dropped Agnes off at her studio apartment in Golden Hill which sat between two Victorians in the shade of a grapefruit tree, a street lined with cars, the yellow lighted windows blinking on in the darkness.

Walking up the brick path under the trees she heard mariachi music from the line of pink apartments across the street—fuzzy, barely there. She could smell onions and garlic frying in butter and a voice was yelling something distant, then laughter followed by frantic noise on TV, the war, or a riot.

Sleepwalking she opened the door, shut it behind her, and dropped her keys on the carpet. She stepped across the bare twin-size mattress on the floor and over her guitar and 4-track machine and a pile of tapes and cables as she pulled off her clothes, then three steps to the tiny bathroom.

The person in the mirror: pale skin, freckles across her nose, soft brown hair swept over her forehead and tucked behind her left ear, longer on the sides than the back, falling into pin-curls around her chin. The face was unsmiling and had empty slate-gray eyes.

She was wrung out, she decided, wrung out and so much older than 22. She ran her hands across her bare shoulders, a new mole on the rise of her collarbone, the tattoo of a one-winged locust on her chest above her left breast.

Agnes cupped her breasts in her hands and looked down at them, her bright pink nipples poking out from between her fingers. She shook her head. She saw the bathmat below her feet, orange, new but starting to wear. Steven’s cum was dried on the inside of her right thigh. Her toenails were painted baby blue. She knew she was pregnant. Somehow she knew. She thought of his cock inside her and the sour smell of his body and her stomach went tight again as it had on the rollercoaster.

Bending down to turn the cold water knob, then the hot—hot to burn her flesh until she was able to forget.

In middle school she was called “the Pale Whale.”

“It was before I lost my baby fat,” she told her coworker Melanie Crenshaw fourteen years later near the dead-center of the country (Overland Park, Kansas) while they sat in the living room of Melanie’s new white townhouse drinking chardonnay with a plate of untouched Ritz crackers and sweet pickles.

“You were fat? I don’t believe that.”

“I wasn’t fat … I was … I was a kid. It was the only time in my life I had tits but I looked awful. In high school my first boyfriend Travis Broadus called me ‘the Pale Princess.’ He meant it as a compliment but … ugh … I hated it. I hated being the Pale Princess even worse than the Pale Whale. That’s why I called the band Pale of Shit.”

“What, Agnes! Oh my god, girl. I didn’t know you played music. Was it any good? I can’t imagine you in a band. Agnes the little secretary in a band, like what?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“What did it sound like?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Come on.”

“It’s dumb. It … it was a hardcore band. I played guitar and sa … screamed. I screamed and played guitar. It was so dumb.”

“Hardcore? Is that like—”

“Punk.”

“Get out. No way. You were so not in a punk band.”

“I was. Yeah, Pale of Shit,” raising her hands above her head and shaking them, “Woo hoo.” Laughing. Then not. “It was during college. I had my own apartment. A car that never ran. Yeah, a band. I was in a band. I was 22 and we broke up when I was … god, like, 23, a year later maybe?”

“Wow, Ags, I can’t imagine you like that. What happened?”

“Life? Growing up? I don’t know.”

“Do you still listen to that kind of music?” Sipping her wine. “If you can call it that.”

“No, not at all,” she said, lying. “I’m not that kid anymore.”

The shower steamed the glass until Agnes was an outline in the mirror.

She stepped into the stall and pulled the curtain closed, the plastic rings clacking.

Agnes shut her eyes and let the water hit the back of her head and run down her shoulders.

Purchase Locust House here.