Locust House Variations, A Weekly Fiction Column by Adam Gnade, Excerpt from an Unpublished Novel

2014, Cold Creek, Wisconsin

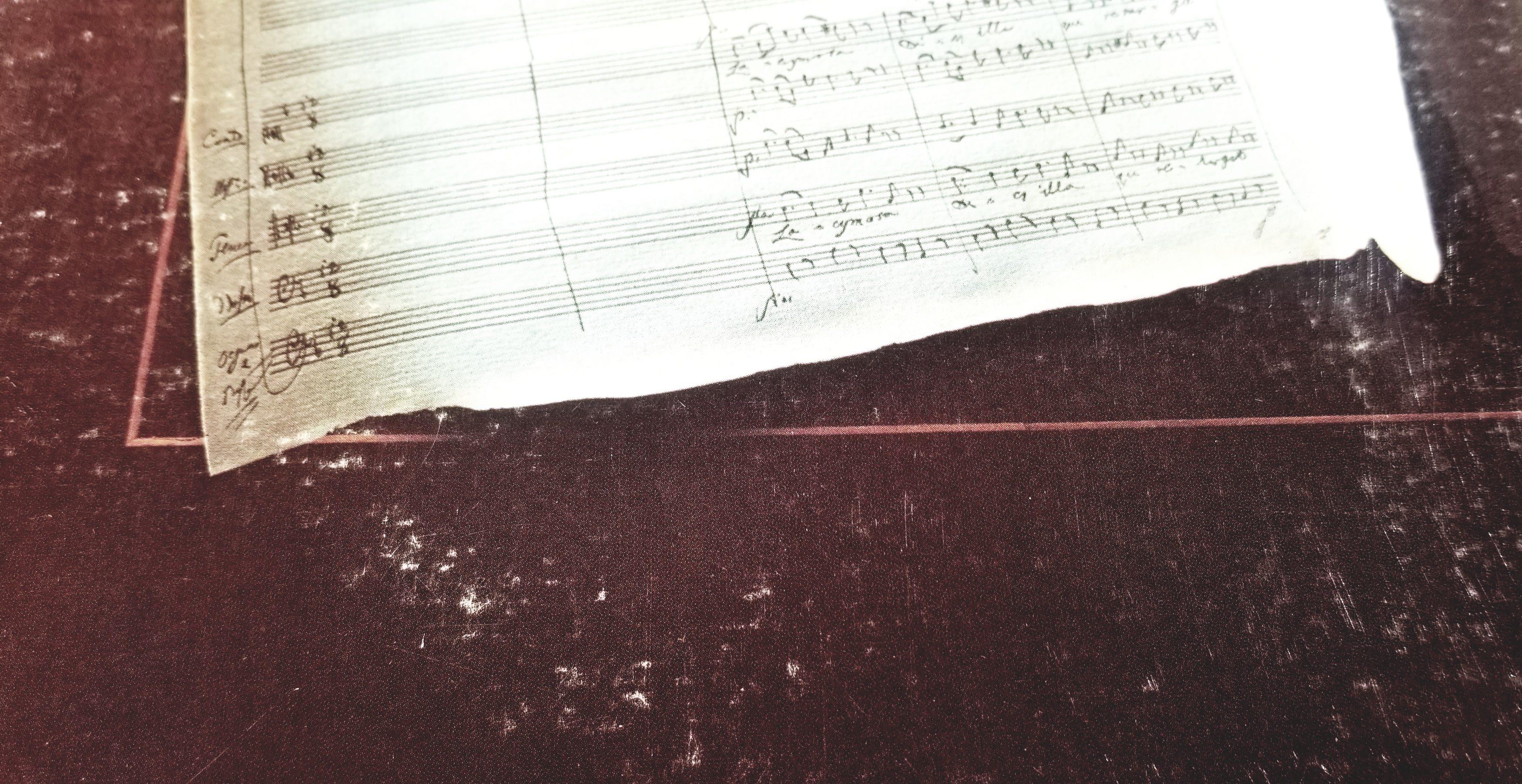

Every night in the cabin (she had been there three weeks) Agnes McCanty, 34, lit a cigarette and listened to side A and B of Mozart’s Requiem, K. 626, performed by the New York Philharmonic (Irmgard Seefried, soprano, Jennie Tourel, alto, Leopold Simoneau, tenor, William Warfield, bass, the Westminster Choir, John Finley Williamson, director). At the end of “Dies Irae” she took the pickle jar of Johnny’s moonshine from the cabinet by the sink (this was the ritual) and unscrewed the lid, sipped it, put it back, then went to sit in the big chair by the window.

Outside it was snowing. It had been since the first week of December. Twenty-one days of silence and freezing mornings and trips out through the snow (wading knee-deep) to the outhouse. The turntable batteries were a luxury, less than an hour a night; no electricity, the red candles on the bedside and window sill glowing. The glass face of the woodstove, dull hot orange in a dark corner.

She imagined putting the palm of her hand on it. Holding it there. Holding it while the flesh cooked into the glass and began to drip down.

At the beginning of “Rex Tremendae Majestatis” she went back for the moonshine, poured a short glass, and began to read A.J. Keeler’s liner notes on the back of the record, starting with: “The summer of 1791 found Mozart physically and emotionally debilitated by years of poverty and continual frustration in his attempts to obtain a proper court position and sufficient popular support.”

By the end of side A, “Lacrimosa,” Agnes McCanty finished the glass and poured another and changed the record to side B, before lighting a cigarette and returning to the chair.

“Domine Jesu” began, but by then her thoughts had gone elsewhere, the smoke curling up from the cigarette in her hand, the black rectangles of window glass showing nothing but her own reflection (her long blonde hair straightened and tucked behind her ears, sunken cheeks, pale) and the red candles next to the turntable.

By “Hostias” (“hostias et preces tibi, Domine, laudis offerimus: tu suscipe pro animabus illis, quarum hodie memoriam facimus: fac eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam: Quam olim Abrahae promisisti, et semini ejus”) she was back home in San Diego stealing “No Shoplifting” signs in sunny thriftstores with Ben Frank and beautiful Marlon Garfield. Marlon, who would later die of a heroin overdose in a fast food bathroom.

San Diego—smoking on porches in Golden Hill. Reading the weekly paper outside bars. North Park house parties. Throwing bikes into the canyon. Drugs and cold pizza in the eucalyptus grove outside the all-ages club while power violence bands played. Olympia—in rundown houses with drizzly forest all around, sleeping in a room where the most famous singer of her generation lived before anyone knew him, his initials carved into the wall and she would lie in bed tracing them with a finger … K … C … deep in a slosh of Vicodin and red wine. Foggy mornings that became gray days that became clear nights with harsh noise shows deafening, like jets taking off. Stoned afternoons in dusty little homes thinking about the quality of the light and feminist theory and the pros and cons of the Skyla intrauterine device. Endless possibilities but nothing to do. Autumn 2004—Oakland by train-tracks and chain-link and gravel and ruin. Taco trucks with metal sides shining and a horn that plays “La Cucaracha.” Gunshots in the night and Ben Frank’s warehouse with his stacks of hardback books on Satanism and the Old West and Norse gods. Flickering candles and someone somewhere learning to play the trumpet alone in a bedroom. Running through the neighborhood back from the liquor store to buy smokes because there was someone following her through a dark section of the block where the streetlights were shot out and it was pitch black and she ran on instinct, thinking Please don’t do this to me, I’m a nice person, please, please, please. Her heart beating and his footsteps beating and his hard breaths behind her. Back to the warehouse, frantic with the keys, fumbling, dropping them, snatching them off the sidewalk then unlocking the big metal gate, slamming it behind her, and collapsing on the concrete, crying in panic but safe,

Doing mushrooms at the AMF bowling alley in Portland and whenever something good happened there was a choir of angels singing “Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Halle-lu-jah!” like some awful comedy film and it was so funny everyone cried laughing (or didn’t, because no one else heard it).

Summer, Los Angeles, mourning Marlon Garfield, listening to the same song on repeat in Albertine‘s beach apartment by the old abandoned middle school where the neighborhood was dead quiet and you could hear the hush of the freeway nine miles away and the streets smelled like eucalyptus leaves.

The song would end and begin again:

“I hear mariachi static on my radio

And the tubes they glow in the dark

And I’m there with her in Ensenada

And I’m here in Echo Park

Carmelita, hold me tighter

I think I’m sinking down

And I’m all strung out on heroin

On the outskirts of town”

Outside her window, a brown palm tree against clear blue sky.

Sweaty Denton, Texas with Byron and Ben Frank and May Stimpson, a gothic Texas nightmare of road-killed deer and fear of cops and running down dark highways on LSD, topless in just boxers and cowboy boots with no stars out and the sounds of the coyotes in the desert. Percocet, hash, pizza, plastic masks, Viking swords, stick ’n’ pokes, vampire teeth.

Chicago—death, evictions, reading St Augustine and Teresa of Avila, reading the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas, reading the Bible trying to find answers, a French Canadian girl with lipstick on her teeth and pale blue hair nodding off on the couch, cold wet sneakers, everyone so young, such babies, baby-faced, well-dressed in their thrift store suits and coats, girls kissing in backrooms, new friends sitting on buggy couches, lice, nits, bedbugs, hummus, pita, heroin, Polaroids, grape leaves, awkward sex, freezing slush.

She thought of beautiful, kind May Stimpson and how she wanted to be her so much she nearly loved her. May, Ben Frank, Byron, and where had they all gone? They said they’d be friends forever but nothing. As nothing as the black through the windows. Now and then the sound of the wind as it whistled around the cabin, the old walls groaning. Everyone gone. Agnes with a month to herself. Her secretary job lost when the hospital administration closed the O.B. department. Cindy from the gym watching the apartment. Her kid with family because Agnes was “deemed unstable and an unsuitable guardian.” Agnes in exile. Or not. A break. To think things through. To reassess and come back to what she once was.

It’s not too late to change, she told herself on the drive up to the cabin, the snow falling and the dark woods all around. You can be that person again and slough off all those years of lifeless life.

“Slough” is the name of the outer layer of skin a snake wriggles out of—she learned that in high school. A snake doesn’t have to plan and scheme and worry itself sick to shed its skin but you will. You don’t have much as far as instincts so you’ll have to be smart about this if you’re going to do it. The one thing you have on your side is brains. Being smart didn’t do a lot of good for you in the past but it’s what you have and you’ve got to make it work.

Side B of the Requiem is heavier than side A—as it should be, she thought—and Agnes saw herself floating in that inflatable raft years ago, the lake mirrored orange-blue as the sunset, jagged pines rising all around, the mellow sky above her, soft air, thinking All is all right. She knew it then but what now? All is not all right. Life gets in the way of your plans. “Life” as a beautiful boy with brain damage, watching the clouds with empty eyes in a room full of flowers. “Life” as a pile of skulls stretching up to the sky—skulls in a pyramid, yellow-white, towering. “Life” as a cartoon-large tombstone reading “Fuck My Life” that falls forward and crushes you flat, blotting out the light.