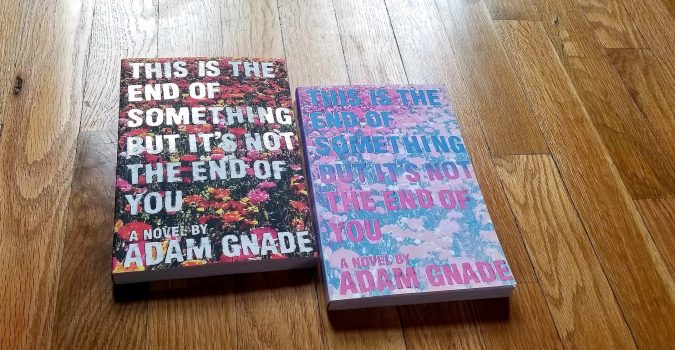

Locust House Variations, A Weekly Fiction Column by Adam Gnade, “Excerpt from the novel This is the End of Something But It’s Not the End of You”

Five years later Julia and I went to Mexico for Valentine’s weekend as a last-ditch effort to save our relationship. Looking back, I spent a lot of my early 20s trying to save relationships that weren’t worth the trouble. I think I knew this at the time—some part of me must have—still, I soldiered on, pushing for a thing that could not be found (or found again, or in the same shape). Julia and I (and most of our friends) were young in that particular way of being young where you are confident in (or even satisfied with) your current state of development and philosophy but unconscious of how desperately unfinished you are; your opinions, morals, and plans are still formless. Though the idea of this, the truth of this would be—to you, in that moment—unfathomable.

There’s a special kind of insensibility that comes to you in your early-young adulthood. It has nothing to do with a lack of intelligence and it’s harmless (until it’s not) and it must be weathered, survived, and grown out of. It comes from not being proven wrong enough or with sufficient repercussions, from stumbling into more triumphs than you’ve had defeats. It’s something you can go far with if you use it well and if others believe in your power as much as you do. This is a glory that is fleeting at best; a normal symptom of later-adolescence rather than any kind of sickness.

Julia and I were good together and then, suddenly, we weren’t. After we broke up I blamed everything on her and I never felt at fault. Now I know I was to blame as much as she was.

So many of us end our relationships as the victim and sometimes that’s true. More often there’s equal blame to share. Julia was fun and angry and full of plans when we met after high school. I loved her intense, careless, freewheeling nature and I ignored the fact that it came from a place of hurt, of being a true victim, the kind that was damaged on a regular basis from a very young age. She had the worst of it from day one—a sexually abusive uncle, a distant father who was a regular customer of local prostitutes, a severely bipolar mother who tried on multiple occasions to kill her when Julia was a baby. (Most of this I learned after we split up. Once it all settled down we became [to our surprise] lifelong friends.)

At the time of our trip to Mexico, Julia and I were something closer to adversaries than a couple. Most of this was my fault. It was my fault because I drank too much. I was emotionally shut-off. I shied away from healthy confrontation and worst of all I was afraid to ask her what she needed. I wouldn’t come to realize this until much later.

When I thought of “fixing Julia and I” it was me fixing her, not me fixing us and most definitely not me fixing myself. I wanted the old Julia back—the one who would sit around her cousin Laci McCarthy’s backyard drinking a 40 while she read bits from Antonio Skármeta or Villaseñor aloud to us. I wanted the one that turned me on to new authors and foreign films and places to eat. I didn’t realize until much later that you have to let people change and that wanting to go back to a previous incarnation of someone isn’t fair to them (not to mention blatantly unrealistic). Julia was growing up. I was stagnating. The combination of that meant we were at odds.

My new friend Chente Ramírez and Julia’s cousin Laci were together and were like (or so it seemed) every couple I knew at the time: “soon to be parted.” Our trip to the Playa Luna Hotel was a double date, my first and only.

The weekend was put together by a magazine I was interning for on my days off from the trolley car diner where Julia and I worked (me cooking short order Italian in the back, Julia at the register and waiting tables). The magazine was a monthly with a loose theme of documenting nightlife culture in photography and jokey (though never outright caustic) society columns. Like a lot of magazines of its kind, it was kept alive on ad revenue from head-shops, dance clubs, cigarette companies, and escort services, yet somehow it pushed on as its competitors dropped by the wayside. It made me think of the last line in Gatsby, about “boats against the current,” though I know now I was taking it out of context. Still there was something there that kept it in business. My friends didn’t like the magazine. It was a different culture than ours. Regardless, it stuck through the years, not changing so much as becoming more what it originally set out to be.

The editorial department was a three-man operation. Taylor Huang, the editor, was a former professional skateboarder from Lakeside who smoked expensive cigars and spent a lot of time at the track in Del Mar. His family was Chinese old money. Textiles and apparel. Josh Roth, who handled ads, wrote the “Man on the Street” column, and took most of the nightclub photography, had been a big acid house guy in Manchester and Edinburgh in the late 1980s and had known Irvine Welsh. Josh Thomas, also known as “Other Josh,” did layouts and wrote a lot of the content. Both Josh and Other Josh wore sunglasses in the office and smoked at their desks. Taylor had a martini station next to his desk and was more often than not happily pickled—clunky rotary phone held eternally between his shoulder and cheek as he managed the business and kept up with his contacts.

The office was on the second story of a beachside stripmall and had windows overlooking the boardwalk and the sea. It was a large single room with a scatter of desks and floor -to-ceiling windows on the south and west-facing walls. In the center of the room was a foosball table no one used. (Mostly it served as a place to set drinks.)

Taylor, Josh, and Other Josh scared me because they were older and because they were cooler in a different way than my friends. For them I was a kid off the street who wanted to write, but wasn’t any good. We had a professional, impersonal relationship—though they were neither with each other. Still they were decent guys and they paid me in Karl Strauss beer vouchers for all the odd jobs I did and let me write a story in each issue. I hustled and they hustled and together we put out a magazine somewhere near the first week of each month, getting by on ad revenue, quid pro quo, and Taylor’s impressive social contacts.

Thanks to a last-minute sponsorship Josh arranged, our group of 42 (made up of friends, business connections, and a few of the magazine’s readers) took a party bus down from San Diego. Like the double date, it was my first and only time doing that. The trip was, if anything, a record of firsts and onlys (or rather lasts, which are a different thing) and now in hindsight seems stamped with a sense of finality, like the closing-off you feel at the end of summer, when fall begins to shorten the days.

–Adam Gnade, author of the Three One G released books Locust House, This is the End of Something But It’s Not the End of You, Float Me Away, Floodwaters, and the upcoming “food novel.”