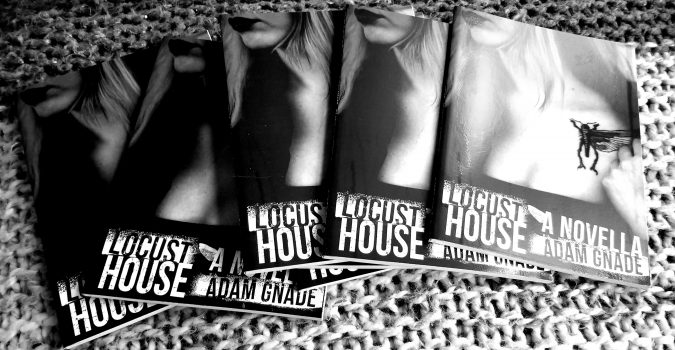

Locust House Variations, a Weekly Fiction Column by Adam Gnade, “The Adventures of Agnes McCanty”

Note: this is an excerpt from the book Locust House

Chapter 1

Looking back, Agnes McCanty would come to see March 29th, 2002 as a day broken into three stages:

1) Standing at the gravesite of Michael the Bear.

2) A view of the sea from atop the rollercoaster then sex with Steven Boone in the backroom of the Halloween store.

3) The final night on E Street and how much she bled and how she felt like an arm held out a speeding car window.

The first: Standing at the gravesite of Michael the Bear in Sherman Heights—his bronze and black Keller-Holland casket like a train car, eye-level for a girl of five foot one, blocking out the sun which glared around it, golden but soft, dusk coming. Agnes thought of the man who lay inside. Michael the Bear, her Father’s uncle, an Irishman (raised in England), though 40 years in the States (Pacific Grove [10 years], Watsonville [12], then San Diego [18]). Before that a pub cook in Coventry (two years) then an RAF pilot in the Second World War (26 months). Michael the Bear, the man who cared for Agnes after her mother passed away (breast cancer) and her father went to jail (for his brother-in-law’s murder). Michael the Bear stepped in, selfless, noble, loyal to Agnes—forever loyal, his defining characteristic. What else? He was strong but wouldn’t stoop to violence (which he told Agnes was unbecoming, as was backbiting, complaining, self-pity, selfishness). He was classy, she decided, yes, whatever classy meant he was that. This had nothing to do with money, which he had, but rather an overriding trait of his upbringing, his generation, and his content of character.

Michael the Bear was a man who liked people, who quietly loved anyone fighting to do a good thing—whatever it was, the goal mattered less than the path there. The final objective itself was unimportant, or secondary.

Agnes stood at the gravesite next to her cousins (who smelled like cigarettes and shampoo) and thought of his face—dark, dignified, high forehead, crow’s feet around the eyes, hair swept back in a mane like a lion’s, a voice like Liam Neeson’s, deep and slow and resonate with bass—a calm voice, husky on the w’s and soft vowels, telling her she was a good woman, that she had grown up well, that he missed her around the house but understood her absence.

The day he died Agnes found the body. The door was locked but she had a key and she stopped in on the way to band practice the day the wildfires swept over East County. The night before she had dreamt of skulls of sheep washing up on the beach—though huge, whale-size, rolling in the surf.

It was a dry day, and it was hot and you could smell smoke and ash in the air from the blaze. Somewhere down the street a dog barked—yipped—as she unlocked the front door.

Agnes heard the sound of the breeze in the eucalyptus.

She pulled the door shut behind her.

The front room was quiet and still and there were dust motes moving in the light of the side-yard window.

She called his name.

The mouth of the hallway was dark—a black rectangle, open, featureless. She stepped into it and called out to him again as she walked down the hall.

In the bedroom Michael the Bear was under the big denim quilt.

He … no, not he, she thought, his body, it, not he, was facing the wall. A giant, six foot four even at his age, a flattened mountain or a cinder cone, motionless. His body was still in a way that the living never are.

The room was cold.

She dropped to her knees.

Michael the Bear was 82 and it was “coming” (her cousin Mary Lynn said on the car ride to the cemetery) but it would never happen today, some other day perhaps, not today, today would be fine, he would be here today. Anyway, why say goodbye to the living? Why sum up your time with someone when their time has not come?

“Hummingbird” was his name for her. Riding on his big shoulders at the Del Mar Fair, age four, talking in her high, piping voice, tiny hands too tight around his neck, but he didn’t mind. He loved her with a burning pride, a strong, tremendous, substantial love; she couldn’t hurt him. No one could. He was a stone, a castle wall, a locked drawbridge but a drawbridge that would open if she (or anyone worthwhile) asked. He was tough without being hard and that was the thing that made her feel safest.

(Continued)